Despite the title of this entry, and contrary to the lack of activity on this blog (hello, last post being the better part of two years ago), I am indeed still alive.

Over the past two years, I have been happily pursuing many and varied musical activities — scoring for films and other media, writing arrangements for concerts and events, orchestrating and doing sheet music preparation for various projects (including the video game Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora), conducting recording sessions, furthering my study of three sizes of viola da gamba (both at home and internationally!) — and have overall been trying to build back my practice as a musical multi-hyphenate in a way that is healthy and sustainable (almost in defiance of industry norms! 😉). I just haven’t had too much to say about them in a way that would be particularly interesting as a blog. Do people still blog anymore?

I am, however, eager to share my latest news with you.

Today, I celebrate the release of my latest composition, In Memoriam (also known by its Korean title, 추도, pronounced chudo), out now on Spotify, Apple Music, and YouTube.

Wait, Korean?

I may be getting ahead of myself. 😅

In May and June of 2024, I took the opportunity to visit South Korea and Japan as a special 40th birthday present to myself. It had been several years since I had travelled anywhere by air, my last time being a quick trip to New York City for the American premiere of The Suitcase in 2018, immediately before scoring Haru’s New Year. It had been even longer since I had flown overseas — a trip to Poland to assist my mentor, Paul Hoffert, with a concert and a documentary in 2016 — and 16 years since I last crossed the Pacific. I had long desired a return to Japan ever since I returned home from my last visit in 2008, and Korea had always been on my travel wish-list — and I figured that since my music had already been there (courtesy of Haru’s New Year screening in festivals in Seoul and Busan), it was long past time for me to follow.

While in South Korea last summer, I finally had the chance to meet one of my mentees (or 후배, hubae), Michael Choi. Back in 2016, having found my work online, Michael contacted me shortly after his acceptance to Berklee in Valencia, where he was about to embark on the Master of Music in Scoring for Film, Television, and Video Games program. He was eager to hear about my experience in the program, and I was happy to oblige. We kept in touch during and after his year in the program, and I am proud to see how, in the intervening years, he has developed into a very fine screen composer in his own right.

In addition to working as a composer, Michael established an orchestral concert series in 2023 called Never Forgotten, held in commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the Korean War armistice. Under the direction of Maestro Hoon Suh, the Grand Philharmonic Orchestra in Seoul performed a program of new works mixed with film music, all themed on aspects of war and peace. Michael shared the recording from the concert with me when I visited him at his professional base in Busan, and he mused about potential future iterations of this concert featuring more international composers in its lineup.

A few weeks later, after I had returned home to Toronto, I received a message from him, on behalf of the Grand Philharmonic Orchestra, commissioning me to compose a new work to be premiered at the second edition of this concert series, Never Forgotten 2024: War & Peace. He explained that the aim of this year’s concert would be to preserve the memory of the Korean War and the Vietnam War, to honour our veterans and those who made the ultimate sacrifice, and, of course, to pray for peace. I was to be one of four international composers invited to contribute a new work to this performance, each of us representing one of the many countries that fought for the United Nations coalition forces during the Korean War; I was, and remain, deeply honoured to have been asked to represent Canada at this concert.

Similar to the inaugural concert, each of us participating in Never Forgotten 2024 would be given a different topic or aspect to serve as our inspiration for our compositions. My commission, formalized several weeks later, was to write a standalone symphonic concert piece, running between 3-7 minutes in duration, reflecting on the sorrow of war, the tears of the innocent, and mourning the lost.

That was it. No picture to enhance. No director’s feedback. No narrative aside from anything I might come up with in my own imagination. No click. No synths or prerecords.

Just me, up to 7 minutes with an orchestra, a poignant (if suitably broad) topic for a brief, and about two months until my first draft was due.

No pressure.

In today’s episode, we will take you inside the Federmusik to examine the compositional process of 추도/In Memoriam, and then in my next entry, I’ll tell you more about my time in Seoul for the rehearsals and performance of the Never Forgotten 2024: War & Peace concert. Happy New Year — or, more aptly, 새해 복 많이 받으세요 — and welcome back to the Podium!

An Immense Responsibility

Immediately, I felt the weight of the responsibility of this commission: a new orchestral work, to be performed by a 57-piece orchestra, representing my home country on an international stage, honouring the memory of those lost in war. I read about the Korean War and Canada’s role in the UN coalition. I thought of my family members who both survived and perished in the Holocaust. I remembered my trip to Mauthausen in Austria, walking in the footsteps of ancestors I never knew. My mind went to all of the current global conflicts and suffering. My heart ached.

Further, while orchestrating and arranging other people’s music for ensembles of all sizes has become a regular part of my work, and for as much as I pride myself in my orchestral skills — heck, the first impression that I make on this very website is me directing a full orchestra! — it had actually been a few years since I had last composed anything original for orchestra, and even longer since I had done so for an actual live one! I couldn’t even remember the last time I wrote an honest-to-goodness concert piece that wasn’t an adaptation of something I had previously written for a film or game!

On top of feeling more than just a touch out of practice, I would be lying if I said that the spectre of iconic orchestral masterworks that are immediately associated with concepts surrounding the sorrow of war (like Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings or John Williams’ theme from Schindler’s List) didn’t loom large in my mind. At all.

This was daunting.

It took a few weeks of reflection to begin getting my ideas in order, sketching out melodic ideas in my notebook (as I usually do), and a few more before I was ready to translate my scribbles into a more useful form and start composing in earnest. I decided to approach this piece as I do anything with this much responsibility: with simple sincerity.

The overall tenor of this piece would be heartfelt and mournful, yet contemplative and understated. I had to take care to never devolve into sentimentality or melodrama, and, for once, keep the orchestral bombast to a tasteful minimum. It would be long and lyrical, owing to my penchant for melody and my chosen approach to the subject matter (and, as an added bonus, knowing that having a strong melody would also help the piece connect well with my Korean audience). Most of all, it needed to come, as composer and Holocaust survivor Leo Spellman (of blessed memory) used to tell me, from the heart.

I drew inspiration from the end of the Book of Lamentations to craft a prayerful melody, and ended up with a meditation on the nature of memory, grief, and guilt born of the sorrow of war. It was my hope that this composition, with its solemn message of peace and remembrance, could help all those at the Never Forgotten 2024 concert join together in a moment of collective reflection.

Theme Breakdown

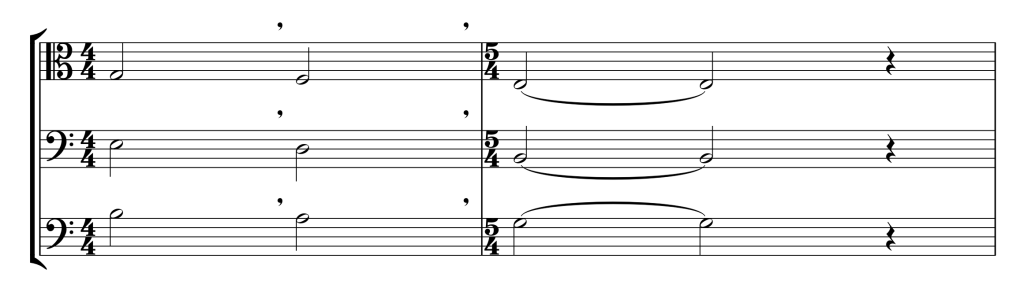

We begin with a solo cello introducing the elegiac main theme, as if in a personal, private prayer:

At first, the melody sounds resolved and self-contained within the first four-measure phrase (beginning and ending on E, the first degree of the scale of our home (or “tonic”) key of E minor). The second phrase takes this idea and builds on it, ending with an unresolved feeling (courtesy of the melody ending on F#, the second degree of the scale; as you will hear in the concert recording, this is supported by a dominant harmony). You may also notice that this melody overall does not maintain a regular time signature, but rather, each melodic gesture flows freely into the next.

If it feels like this melody is syllabic and could potentially support a text setting, your sense is correct. I drew my inspiration for this A Theme (the above excerpt and the rest of the melody that follows) from Lamentations 5:21 (“Take us back, O Lord, to Yourself, and we will be restored; renew our days as of old!”) — more specifically, the Hebrew text: Hashivenu, [Adoshem] elecha, vena shuva; chadesh yameinu kekedem.

The free-flowing opening phrase functions almost like the incipit of a chant, as if inviting the congregation to join in with a reply. Accordingly, the rest of the strings enter with harmonic support during the second phrase of the above melody, as if more voices are being raised to support our cello soloist.

A Theme, Part II

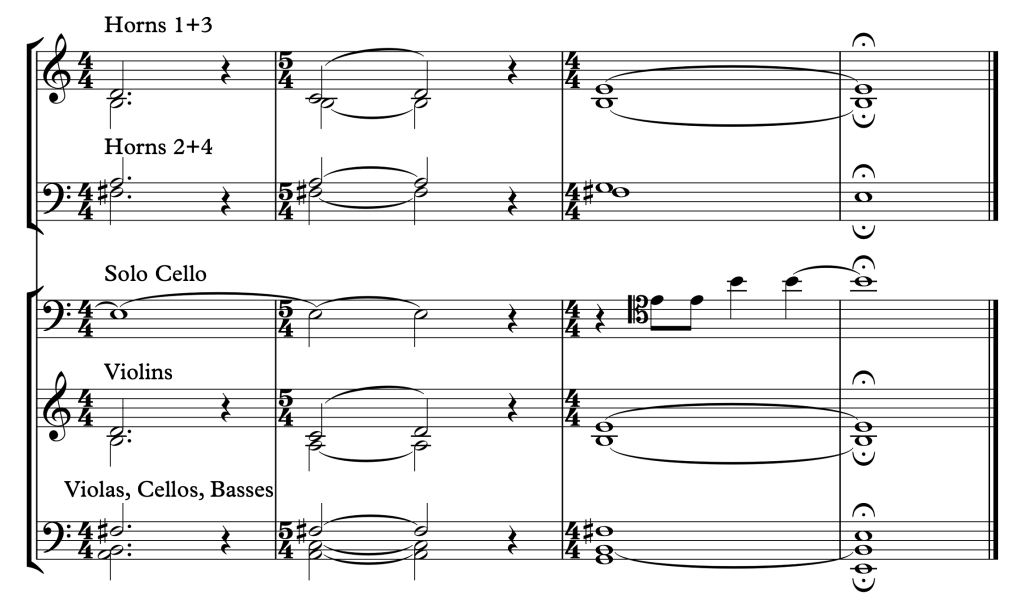

The first violins take over the melody, and, supported by the second violins, violas, celli, and horns, extend this initial idea into a new melodic phrase:

As you may hear, this second phrase also ends unresolved, with the melody ending on the 5th degree of the scale (supported again by a dominant harmony). The more theory-minded of you may also realize that the first and third bars above outline F major (reinforced by the harmony, which you will hear in the concert recording), which is not within our tonic key of E minor, but is a tritone away from the phrase-ending dominant of B major (pay attention, class; this comes back later). My use of modal mixture, hopeful and uplifting as it might sound, begins to destabilize our harmonic centre, if only temporarily.

We then return to the beginning with a repeat of the main theme in the woodwinds, with the strings providing harmonic support. Specifically, I call for the alto flute, the English horn, and the second clarinet in unison, together with the second bassoon an octave lower, all essentially in one voice. That we hear this played by a quartet comprised of the second or auxiliary players, rather than the more soloistic principal players, indicates that this statement of the melody is intended as an echo of what we just heard in the solo cello (behold the power of orchestration!).

The principal players get their due in the next phrase as the texture grows into the full woodwind choir, in a lush and rich chorale-style harmony, supported by horns and strings. The solo cello also returns with a heartrending countermelody, waxing larger and louder to a moment featuring the full orchestra for the first time.

After this miniature climax, I shrink the texture immediately to create a more intimate, introspective moment as the strings repeat the second part of the melody, featuring the second violins, violas, and celli in close harmony while the first violins gently soar on top. This is followed by a little echo in the rest of the orchestra.

A Theme, Part III

We then head for the final strain of the main melody, led by the solo cello playing high up in its tenor range. As you may hear, we finally reach a melodic resolution (ending on our tonic note of E) — though not quite a harmonic one just yet.

This idea is repeated and developed by the strings and woodwinds, with melodic variation expanding the range and scope… and then, before we reach the end of the melody and a satisfying conclusion, the tone of the piece turns darker, as if a distant memory stirs. Fragments of the melody echo through the orchestra, alternately mysterious, mournful, and martial. As we go deeper into the memory, the soundscape transforms to a sombre, funereal march beneath calls of pipe and horn, modulating from our home key of E minor to the harmonically distant key of B-flat minor (which is a tritone away! Aren’t you glad you paid attention? 😉).

A New Theme Emerges

The tension gives way as the core of this forgotten memory unlocks. We hear a new melancholic theme on solo horn, supported by strings, which is then echoed by the choir of woodwinds. While this second theme is similar in its flowing melodic arc, it is more regular in rhythm compared to the principal theme of the piece.

I had been honestly uncertain about pursuing this theme in the context of this piece until I realized that it scanned fairly well with the text of the (admittedly less-performed) final verse of the Book of Lamentations: “For truly, You have rejected us, bitterly raged against us” (or, in Hebrew, Ki im-ma’os me’as’tanu, qa-sap’ta alenu ad-me’od).

Our solo cellist returns, ruminating on this new theme, which leads to a cascade of repetitions as the melody swirls through the orchestra, growing in volume and mass each time. As the orchestra rages its way through a series of harmonic modulations, the solo cello bursts forth, overcome with emotion, shouting the initial motif of the A Theme with passionate fervor.

Coda

We snap back to the present moment, where we are left with a raw feeling of loss. The piece concludes with the lower strings in close harmony presenting a slow, three-chord, cadential sequence, back in our original tonic key of E minor. Space is left for a melody that remains conspicuously absent. We repeat the chords, and we hear the echo of the first motif of the piece, now in a quintet of second and auxiliary woodwinds:

We play the chords again, thickening the texture with the second violins, with the first motif echoed by a trio of two horns and a trumpet. The first violins join on the fourth repetition of these chords as the solo cello leads us to a quiet conclusion and one final statement of the initial motif.

I had my first draft of the score finished by the beginning of November. After pouring out every last ounce of emotion onto the page, I was overcome with an overwhelming feeling of emptiness. In the face of global events, despite the copious tears shed while writing, my piece suddenly felt at once apt and yet sadly insufficient.

Had I done enough? Was it even interesting? Would it connect with the audience?

All that was left to do was prepare the piece — and myself — for our journey to Seoul for the concert premiere on December 12, 2024.

To be continued… / 계속…

Are there any other aspects of the composition you’d like me to expand on? Let me know in the comments below!

Hi David!

Thank you for sharing your process of creating this powerful music!

I always enjoy reading your newsletter. I know I do not interact with it much, but I am reading and finding it helpful and motivating to pursue my own projects.

I hope you do not mind, I have forwarded your story to my composition student Mohamed (23 y o).

I think he could benefit his creativity from connecting with established composers such as yourself.🙏🏻😊

Thank you once again for sharing your creative process with us so openly and eloquently! I appreciate it always!

Wishing you a good and peaceful week, full of creative inspiration.

~Vira