Welcome back to the Podium! In this episode of Inside the Federmusik, I will be recalling my experience of scoring my first feature film, John Lives Again, a romantic comedy written and directed by Anthony Furey.

(…and no, before you ask, this is not the sequel to John Dies at the End. Sheesh.)

I was introduced to Anthony through a mutual friend, and we corresponded in February of 2015, while I was still in Los Angeles. He in turn introduced me to the story of John, a coming-of-age film in stylistic homage to those fun Woody Allen/John Hughes films that you remember from the ’80s. John is a quirky, awkward everyman (portrayed by Randal Edwards) who, pushing 30, realizes that he needs to get his life together, outgrow his penchant for bedding a string of one-night stands by means of outlandish tricks and ploys, and wind up in a steady, committed relationship — possibly even in that order. John is a hopeless romantic… or maybe he’s just hopeless.

Anthony indicated that he had licensed a number of ’80s Canadian pop/rock tunes, and desired the score to be written in a similar vibe. Normally, based on my largely orchestral portfolio and classical training, one might readily assume that I am not fluent in the ancient art of rocking out. However, that clearly did not preclude me from consideration as the composer to help bring John to life.

I will disclose at this point that in addition to not regularly writing music inspired by the pop/rock repertoire of the 1980s (even though I’m as much a fan of it as the next person), comedy films, let alone romantic ones, are not usually my first choice of cinematic fare. Yet, in reading the script, I found Anthony’s narrative surprisingly engaging — even laughing in (what I assumed were) the correct places! — with the characters practically dancing off the page. I promised myself initially that I would read no more than five pages, and then found myself at the end before I knew it. As my friends and colleagues can perfectly attest, if a romantic comedy could make me laugh, then I knew that there was something special at play here. I was sold.

I approached this project as I would any other: not merely getting to know the characters and the world of the film, but also getting to know the director and understanding the creator’s perspective and outlook. Anthony and I took our first in-person meeting the day after I returned home to Toronto at the end of March, and we arranged a spotting session to determine the placement and style of musical cues a few days later. We agreed on the amount and kind of music required, determining a fair amount based on the narrative and dramatic needs, relative to the time and budget available. Even though Anthony and I had made our initial correspondence a month prior, it was only then, staring down the barrel of hard post-production deadlines, that we were ready to discuss the film in earnest. There wasn’t a moment to lose.

The Making of a Theme

The next day, I began the process of what we in the industry politely refer to as “messing around.” This includes performing any research that might be required, considering sonorities and musical textures, building my compositional template, working out themes and preliminary musical ideas — essentially, the film composer’s equivalent of looking at fabric swatches or shopping for ingredients. During our spotting session, Anthony had requested that I compose a theme for our protagonist that was “poppy, rocky, and fun,” but also adaptable enough to be presented appropriately in quieter, more introspective moments. Simplicity would be key.

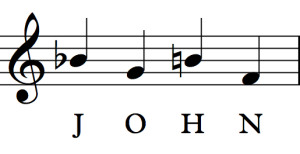

There are, of course, many ways to generate a theme or motif. For John’s theme, I elected to create a musical cryptogram — that is, a matrix assigning letters of the alphabet to certain pitches — to spell out JOHN LIVES AGAIN. It seemed about as good a starting point as any. I decided that my row would represent the standard scale tones A through G, but also H (German for B natural, with the letter B representing B-flat), before repeating: I through P, Q through X, followed by Y and Z.

How does something like this work?

For JOHN, the letter J aligned with the note B-flat, O with G, H represented B natural on my initial row, and N aligned with F. Therefore, JOHN is spelled using the musical notes of B-flat, G, B natural, and F (see the musical example below).

The thing about musical cryptograms is that they stand alone pretty well, like BACH, DSCH, or even DFED — I’m quite partial to that last one — and if you can either fit it into an appropriate context or build one around it, then more power to you. I’m all for a good, clever musical joke when it works. Sometimes, however, it doesn’t.

As a melody, something about that didn’t sit quite right with me. To be specific, the particular interval between my H (B natural) and N (F), a tritone, did not seem appropriate for a “fun” romantic comedy theme. Perhaps it might work for a thriller or horror film, but not here. Sorry, John.

With a little minor tweaking to soften out the H to a B(-flat) (multilingual musical pun intended), it became a little more palatable for this context.

Next, on to LIVES. On my matrix, the letter L aligned with D, I with A, and V with F. “Es” is German for E-flat (the “S” in the DSCH example I mentioned above), so I took that as a sign. Together, they spell a D-minor chord with an added flat-9. Groovy.

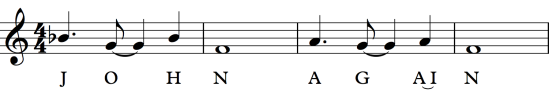

For AGAIN, A and G were already notes on the initial row. I aligns with A, which I opted to merge into one note, and N, as above in JOHN, was F.

I ended up with two four-note motifs, JOHN and AGAIN, with a cool-sounding chord in between. When “JOHN AGAIN” is played in succession, they form what would become John’s Theme:

You can even sing along with it, too! “John Lives A-gain! John Lives A-gain!” All that remained was to hope that the director liked it.

Most of the score cues in the film are based on one motif or the other, if not the whole eight-note theme. The thing that I like about simple motifs is that they are, as per the director’s request, eminently adaptable. To expand my options beyond simple statements of the vanilla JOHN and AGAIN motifs, I considered other melodic variants, and worked out what modifications would be necessary to have them playable in consonance with other harmonic modes. I consider this manner of adaptation to exist on a spectrum of tools ranging from a surgical scalpel (for minor adjustments) to a baseball bat (for more drastic reconstructions).

LIVES was more present in earlier drafts of cues, but it was relegated to a single yet prominent statement related to a character being rushed to hospital. It felt strangely appropriate.

As my work on the film progressed, I found that for scenes that were primarily driven by John’s thoughts on Vanessa (portrayed by Erin Agostino), the object of his affection, I gravitated towards using the AGAIN motif, whether by itself or riffing on it. On further consideration, John’s relationship with Vanessa has a certain again quality to it: John is floored by a pretty girl again, he botches a date again, he tries to win her over again, and so on. In retrospect, I find it strangely appropriate that things worked out this way, with Vanessa, the intended other half of John, being represented musically by the AGAIN motif, the “other half” of JOHN, and the two motifs fitting together to become a full theme. (Everyone together now: Awwwww!)

The Sound and the Furey

Anthony and I considered that the licensed tunes represented not only John’s external musical preferences, but also his internal soundtrack: for example, his gaze fixes on a pretty girl and we hear an excerpt of a new wave ballad. Yet, a strict emulation of those songs would have been musically redundant. What I brought to the table was ’80s rock through a film scoring lens, incorporating certain elements of jazz and following a dramatic, narrative arc to enhance the emotional content of the scene. Anthony and I maintained a healthy dialogue over the course of my cue demos, bouncing ideas off one another. In terms of instrumentation, we decided to use a live rock band setup (guitars, bass, drums, and synth/keys) that would remain consistent throughout the soundtrack.

Through the writing period, Anthony expressed a preference for the cue demos that were written in more of a straightforward rock style over the ones that attempted to be softer, more dramatic, or simply more film score-esque. Approaching this score and this genre of music with the perspective of “They’re only notes, they’re only instruments,” it seems as though my orchestration — or, in this case, rockestration — chops came in handy.

A 33-Hour Clock

After a two-week whirlwind of writing and rewriting, Anthony approved the final cue, and it was onward to recording. Early on, I contracted my friend, Andrew Ross Geladaris, to record lead guitar and bass for me. I then sought to recruit additional personnel to round out the team. One of the best things about my experience at Berklee in Valencia was the connections that I made to both emerging and established professionals all over the world. I contacted Pablo Schuller, one of my instructors and the Senior Engineer at Berklee in Valencia, who was fortunately available to be the mix engineer for the score. I reached out to Tom McGeoch, a Los Angeles-based Berklee grad whom I also knew from my time in Valencia, to be my drummer. Tom connected me with Jake Valentine at Village Studios to be our recording engineer, who in turn introduced me to Billy Centenaro (who also served as our assistant engineer) and David Dudley Corwin for rhythm guitar and additional bass, respectively.

Drummer Tom McGeoch rocks the kit at Village Studios during our recording session. Photo courtesy of Billy Centenaro.

Owing to the limited time available, I rushed from a day of tracking Andrew on guitar and bass north of Toronto back to my midtown home studio in time to remotely produce Tom’s drum recording session in Los Angeles, which was scheduled from 10:30 p.m. to 1:30 a.m., Pacific Time (or, in my neighbourhood, 1:30 a.m. to 4:30 a.m.). We adjourned until the next evening (albeit not as late) to track Billy and David, giving me time to edit the first day’s recorded material and have it ready for to Pablo to mix in Valencia, Spain, by the time he woke up. So it went for the next few days: I received most of my recorded material while I napped, edited it while Pablo was either sleeping or working at Berklee, and he set aside his evenings (my afternoons) for mixing my score. I envisioned us chasing each other around the clock as we tumbled through time. Perhaps that was the sleep deprivation talking.

Engineer Jake Valentine (left) helms the tracking session for guitarist Billy Centenaro at Village Studios, while I produce remotely via Skype. Photo courtesy of Tom McGeoch.

For those of you who are keeping score, there is a 6-hour time difference between Toronto and Valencia, and 3 more hours between Toronto and Los Angeles. As the coordination between my team members who were recording in LA and mixing in Spain yielded an absolute value of 9 additional hours, I considered that I was operating on a 33-hour clock. It worked out pretty well, all things considered.

It’s the Final Mixdown!

After indulging in my first full night’s sleep in nearly a week, I delivered Pablo’s final mixes to REDLAB Digital, our post-production facility, where I met and worked with JR Fountain, our re-recording engineer (also known as a “dubbing mixer”). I was invited to stay for the mixing days and, alongside Anthony and our post-production supervisor, Michael Liotta, supervise the placement of and final volume tweaks to my music.

The first cue that we tested in the dubbing theatre was the one that I had written for the ending credits. As the drums and guitars roared from the speakers in the mixing theatre in the opening moments of the cue, Anthony turned to me and summarily offered a fistbump and his congratulations. Delivering my first feature film score on my last day of being 30 was a pretty nice birthday present, if I do say so myself.

I owe a debt of gratitude to Anthony for offering me the opportunity to collaborate on our first feature. I’m definitely looking forward to the next one. Scoring John Lives Again sincerely felt like my final test to mark my re-entry into the Toronto film community, and, more importantly, the true cumulation of the training and experience that I received through my time both at Berklee in Valencia and in Bear McCreary’s studio.

After three mixing days (of which I attended two), I joined Anthony and other key creatives on the project in the mixing theatre at REDLAB to watch the final playback (or “the dub”) of the film, in which we locked down the audio. Handshakes and fix notes were shared around the room.

My final fix note from the director: “My wife has a bone to pick with you because I can’t stop singing your theme.”

I guess he liked it. 😉

JOHN LIVES AGAIN is currently exploring the film festival circuit and seeking avenues for distribution.