To mark the premiere of Sergio Hernández Elvira’s Cruzar el umbral (Crossing the Threshold) at the 61st annual Valladolid International Film Festival this week, it is my pleasure to bring you inside the Federmusik to learn more about the composition process for this short psychological thriller.

Cruzar is the story of Laura (portrayed by Gisela Arnao), who awakens one morning to find that her husband, David (Carlus Fàbrega), has left without saying a word, leaving her and her daughter, Sara (Irene Quero), on their own. Laura embarks on a journey of recuperation through visiting a psychologist (Luis Carlos Llinàs) and coming to terms with her own internal demons to eventually overcome the trauma of her husband’s disappearance.

Initial Stages

Sergio and I met in March of 2014, while I was a Master’s student at Berklee College of Music, Valencia campus, and he was a student at Escola Superior de Cinema i Audiovisuales de Catalunya (ESCAC). Even though we were both impressed with each other’s respective body of work, the timing was not right for a collaboration at the time. We resolved to remain in contact for when future opportunities to work together would arise.

A little more than a year later, Sergio contacted me about a thriller that he was developing, describing it as a “ghost story.” However, it was not until he was satisfied with his script, in October of 2015, that he was ready to formally approach me to be his composer. I indicated my interest in joining him, and he promised to follow up with an English-translated script so that I could begin generating ideas. However, through the process of finalizing pre-production, preparing for principal photography, and launching the film’s crowdfunding campaign, a script was never actually sent. That said, I am told that the changes between what was written and what was filmed would have mitigated its utility for my purposes.

I received the fine cut of the film in early February of 2016, and booked a spotting session with Sergio – a conversation in which the director and composer (and/or their respective designates) determine the placement of music – shortly thereafter. After watching the film a couple times on my own, we reviewed the film together and, via Skype, discussed his musical desires. He expressed some trepidation, for fear of not having an appropriate musical vocabulary to describe his intention. To his relief, I insisted that he speak to me in terms of emotion and reaction, for me to strive towards the goal of eliciting a certain response from the audience with my music.

In every film that I score, my objective is to enhance the viewing experience for the audience by evoking mood and accentuating the dramatic notes that have already been captured by the direction, acting, cinematography, and editing. What remains for me to state, then, is largely subtext, expressing the innermost thoughts of (admittedly, the director, but more poetically) the characters on screen. Essentially, my job is to hear things that are not there.

Laura (Gisela Arnao) hears things that are not there… or are they?

By the time I receive the fine cut of the film, the editing process is almost complete: the director and editor have selected and trimmed their choice cuts – the best takes – to go into the film, with only minor adjustments left to be made. Sergio and I viewed this print of Cruzar with the understanding that no substantial changes would be made afterwards, so I would be free to begin scoring without fear of the playing field changing under me. As a composer, I intuit a substantial amount of information from the film itself, in addition to the narrative: the facial expression and body language of the actors, their gait when they move and how the camera moves with them, the cinematography and mise-en-scène, the editing, and so on.

The Sound of Cruzar

After a spotting session, I normally spend at least a few days to consider the direction that has been discussed and to plan my musical strategy. This involves considering themes and motifs, sonorities and textures, and building a compositional template, particularly if it makes sense to keep certain musical elements, like instrumentation, consistent from cue to cue throughout the score.

I had in mind to recruit a string quartet to provide a live recorded element to the soundtrack, which would be blended and mixed with prerecorded (virtual) instruments. I took the opportunity to reconnect with violinist Tanya Charles, my classmate from my years as an undergrad at the University of Toronto, Faculty of Music, who is now a member of the Odin String Quartet. Together with violinist Alex Toškov, violist Laurence Schaufele, and cellist Samuel Bisson, they tackled my score with verve and aplomb, and it was a pleasure to have them under my baton.

I direct the Odin String Quartet during the recording session for Cruzar at Kühl Muzik in Toronto.

In my discussions with Sergio, I related my understanding that inasmuch as Cruzar is a ghost story, it is more importantly a story about life, which therefore deserved to be told with a live element in my palette. For all of the advancements in MIDI and virtual instruments, nothing compares to live performance for instilling a sense of realism with which an audience can connect.

The sound of a string quartet in particular produces a certain intimacy that is not found in a larger string ensemble. Even when supported by a string orchestra, the ear is drawn to the texture of solo strings. My initial instinct for the score was to take more of a subtle, sad approach, which featured the string quartet more prominently. However, in response to my first round of cue demos, the director and his team felt that the tone of the story required more musical intensity and a fuller sound.

In addition to string quartet and string ensemble, I decided to round out the instrumentation with piano, synths, and some subtle percussion, notably a virtual instrument made from tuned lightshades (which sounds remarkably like a hang drum).

Musical Motifs

As you may recall from my writing about John Lives Again, I am a proponent of using recurring themes and motifs to give a sense of continuity and congruity to my scores. Through the process of discussions and demos with Sergio, it was agreed that grandiose, sweeping themes were not the appropriate solution for Cruzar, but rather a series of smaller motifs, as if I am dropping clues about the mystery contained within the plot alongside the director.

As you also may recall from my score to John Lives Again, I like using musical cryptograms to generate these themes and motifs. For this score, I used a combination of letters, solfège (do, re, mi, etc.), and leaps of logic to generate two of my motifs: one for Laura, our protagonist, and one for her missing husband, David.

Laura’s motif is composed of just two notes, representing the syllables La-Ra: La is the note A in fixed-do solfège, and Ra I consider to be a flattened re (the note D), which then corresponds to the note D-flat. Laura’s motif is initially presented subtly and in the background, but grows to prominence towards the end of the film as the plot shifts and twists.

(Technically, in the score, I spelled the D-flat as its enharmonic equivalent, C-sharp, for the sake of legibility.)

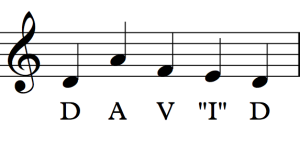

I wrote two versions of David’s motif (not that I have the slightest bias in this regard, or anything). The first one borrows from the cryptogram chart that I used for John Lives Again, in which the letter I corresponds to the note A, and V with F. Thus, in this version, DAVID is spelled using the notes D-A-F-A-D.

The second one replaces the second A with an E. Musically, this connects the F to the final D in stepwise, scalar motion. In Spanish (and other languages), the pronunciation of the letter I resembles the long-E sound in the English language. As well, the emphasis is on the second syllable of David, so after hearing it consistently for a year in Spain (and again by Gisela Arnao repeatedly in this film), I haven’t been able to get the strong “ee” sound out of my head.

(…or did I just want an excuse to include a Da-Fed cryptogram? I’ll never tell. 😉 )

We hear both of these versions during the second score cue, in which Laura and Sara search fruitlessly for David. The first one appears when Sara reports that she cannot find her father in her room (which Sergio said imparted a childlike quality to this motif). We hear the more wave-like second version shortly thereafter as Laura continues her search through their apartment. The difference is subtle, but it is there.

The Mystery motif, which is heard in full at the end of the opening sequence and recurs through Laura’s and Sara’s search for David, is the closest thing to a theme that we have in this film. This motif is composed of a pair of six-note phrases, almost identical except for the last note. The arc meanders up and down, in an inquisitive fashion, as if searching high and low for answers. I furtively introduce this motif near the beginning of the film: when Laura wakes up, we hear the second through fifth notes played on the cello, then doubled an octave higher on the viola.

Laura is left with a mystery, and the motif to go with it.

Interestingly, when I initially wrote the opening cue, my intention was for the full statement of the Mystery motif to be heard over a shot of Laura standing on the street outside her apartment building, leaving her (and the audience) with the mystery born of the inciting incident of our plot. Instead, when the film moved on to the final mix stage (in Barcelona), the timing of the opening credits had changed, and the cue was placed a few seconds earlier than intended. This shift causes the intensity of the scene to seemingly build sooner, with the full Mystery motif heard over a shot of David at the bottom of the stairs as Laura chases after him. This musical highlighting of the departing David still works from a narrative and dramatic standpoint, but it ultimately creates a different meaning for the viewing audience than what had been originally planned.

The Life and Anatomy of a Cue

With my notes from the spotting session and the director’s emotional roadmap in hand, I set to congeal my ideas for three of the five cues: the opening sequence, a false jump-scare moment, and the dramatic reveal at the climax of the film (cues 1, 3, and 4, respectively). Rather than write the score in strict chronological order, my plan was to compose the music for these three key scenes first, so as to have an adequate amount of material to show the director in a preliminary demo session. Receiving feedback early in the writing process on whether I have adequately captured the director’s intended tone is essential to a smooth and positive collaborative process.

The fourth cue, “Páginas vacías” (Blank Pages), began its life as a testing exercise for the sound of a reversed piano tone. As a significant portion of the final third of this cue is told in flashback, I wanted to associate the tone of the reversed piano with recalling, unearthing, and coming to terms with a previously-suppressed memory (which I will not spoil here).

I wrote a simple but poignant three-note motif for this flashback sequence (which I will specifically not discuss because it contains a spoiler – in English, anyway). I recorded this motif on piano with the notes in reverse order, then reversed the audio recording of this retrograde motif, which resulted in the tones playing back in the proper order and sounding like they were building towards the note being struck. I lined up this reversed recording with another recording of the notes in proper order, giving the effect of the tone being played, then melding and swelling until it bursts into the next note in the sequence.

The test accomplished the effect that I was looking for. After completing the final third, I worked my way backwards to the top of the cue. It was ready to demo.

…and then the director decided to recut the scene to change the pacing and the emotional tenor of the sequence. Remember: I had my initial impressions based on the spotting session and the director’s ideas, but sometimes, the playing field changes after all.

I will continue to avoid giving spoilers, but I will say that the recut version tells a different story. Key pieces of information were removed or reordered. The sequence runs shorter. However (and luckily), the final third of the sequence was untouched, and feedback to that segment was essentially positive – “we like it, but give us more” – so the effort put into testing and implementing the reversed piano at the beginning of this exercise was not wasted.

I pretty much looked like this when I was reviewing my notes from the director.

When Sergio and I spotted this scene for music, we were of two minds as to where to begin. The first option that we considered was to start the cue over a shot of Laura, alone in her apartment with her frustration and desperation (seen above). However, the director wanted to experiment with the final thrust of the film beginning about 20 seconds earlier, when Laura is meeting with her psychologist and Sara has tagged along.

In this preliminary sequence, Laura indicates that Sara (for the first time in the film) is shy, and might open up to him if she is given a candy. The doctor obliges and we closely follow his hand as it lifts the candy dish, passing it towards the two on the opposite couch. As Sara reaches out, Laura plucks a candy from the dish and puts it away, ostensibly saving it for later. This is the first moment in the film when we get an inkling that something might be unusual as far as Sara is concerned.

I wish I could say that scoring this scene was like taking candy from a…

Initially, I felt that the visuals were strong enough to carry the scene on their own, and was concerned that including music over the tracking shot of the candy dish would alert the audience to the fact that something was out of the ordinary. After all, as our conventional reality is decidedly not awash in dramatic, non-diegetic underscore, one role of music in film is to communicate the notion of fantasy. The deliberate use of silence, then, is used as an element to convey reality, as it connects more closely with our own non-musical everyday life. With stark silence, in other words, the pretense of fantasy is dropped.

In the interest of keeping our options open, we agreed to lock down the main part of the cue first, with Sergio allowing me to come back later and try out some ideas for an opening that could be grafted onto the beginning of what I would have already written. By the time Sergio granted his approval for this cue, we both agreed that the shot of the doctor offering Sara the candy dish felt empty without music. Something had to go there, but it could be neither too subtle nor overt, neither could it be too childlike nor dark. No problem, right?

I tried many ideas, most of which were not even sent out for demo. In response to the few that I sent for feedback, Sergio suggested that I take the opportunity to set up something musically for a payoff later in the cue.

Of course! This entire climactic sequence itself, starting at the doctor’s office and ending with the dramatic reveal, follows the tripartite structure of hook, build, and payoff, functioning as a microcosm of the entire film. There was only one possible solution: the three-note motif that plays during the final third of the cue.

Specifically, I built the introduction to this cue by using the melody that grows out of the three-note motif, right at the end. When the melody is heard in its fully-realized form at the end, it serves as a callback to the moment shared over the candy dish, creating meaning for the viewing audience. In addition, as if my initial concern about flagging this moment as unusual was insufficient, Sergio specifically requested that I try ending the melody with a wrong note, to further telegraph to the audience that something was wrong.

Having taken several attempts to produce the finished version, I can report that hitting the “right” wrong note is harder than it seems.

Team Cruzar (L-R): Gary Honess (engineer), Alex Toškov (violin), Laurence Schaufele (viola), David Federman (conductor), Samuel Bisson (cello), Tanya Charles (violin). Photo courtesy of Elyse Maxwell.

I extend my gratitude to Sergio for affording me the opportunity to score his graduating thesis film, to Berklee in Valencia and ESCAC for facilitating our meeting in the first place, to the Odin String Quartet and Gary Honess of Kühl Muzik for a fabulous recording (and putting up with my bad jokes in multiple languages), and to all of our Verkami backers for making this possible.

CRUZAR EL UMBRAL premiered at the 2016 Valladolid International Film Festival.